“Climate change is happening,” she says; “it’s real, it’s urgent.” The speaker is Paola Gianturco, a strikingly pretty octogenarian photojournalist/author, retired from a distinguished business career but decidedly not retired from anything else.

Adds her co-speaker ; “I learned about the water cycle (the continuous movement of water within the earth and atmosphere) and the carbon cycle (the process in which carbon atoms continually travel from the atmosphere to the earth and back) in fourth grade.” This would be high school freshman Avery Sangster, pointing out that those two cycles are keys to climate change.

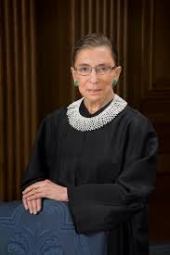

The remarkable grandmother/granddaughter author/activist team spoke recently at an event celebrating their recently released book COOL: Women Leaders Reversing Global Warming

The two spoke of the urgency of climate change in real-time stories. Alaska’s indigenous Inuit people, for example, have lived for centuries on the ice of the Arctic and subarctic regions where temperatures now reach 78 degrees and higher. “I’m not paralyzed with fear,” Gianturco says. She and her equally fearless granddaughter don’t want anyone else to be paralyzed; what they want is action. In search of climate action — and stories — they interviewed and photographed women and girls around the world who are “using intelligence, creativity, energy and courage to help stop global warming.” COOL documents the dedication and successes of several dozen of those women and girls.

They found, for example, Erica Mackie, Co-founder and CEO of GRID Alternatives, headquartered in the San Francisco Bay Area. Asked what’s special about her company, Mackie told the authors, “Well, for starters, it’s the only nonprofit construction company on the planet that’s focused on combating global warming, racism, economic inequality and gender discrimination.” The COOL women don’t tend to think small.

In Sri Lanka they found several women working with Sudeesa (Small Fishers Federation of Sri Lanka) who were among 15,000 Sri Lankan women planting mangrove trees. Should you think these are simply pretty trees that help the local population by attracting fish, “mangrove trees sequester about five times more carbon dioxide than other tropical trees,” while also burying carbon dioxide under the soil.

The information and quotations in this article are all from COOL: Women Leaders Reversing Global Warning. And this is only a small piece of the climate education available in Gianturco and Sangster’s colorful book.

Back in the U.S. again the photojournalist/authors found Miranda Massie, founder and Director of the Climate Museum in New York City’s Soho district. Massie credits her own “climate crisis unease” to Hurricane Sandy, the 2012 storm — still the largest Atlantic hurricane on record — that, according to Wikipedia, left 233 people dead across eight countries and did more than $70 billion in damage. “Our genius, inventiveness, ambition and creativity caused this climate crisis that could obliterate civilization as we know it,” Massie says. “It’s the greatest challenge the human species has ever encountered.”

If the above isn’t enough to inspire you to become a climate activist, this reporter recommends ordering a copy (or two or three or more for your friends and family) of COOL. On the inside page there are even QR codes you can scan for six ways to help reverse global warming. Super cool.

I was born without a left brain. Well, maybe a tiny rudimentary piece of left-ish cortex is in there. Even if the whole left brain/right brain thing is indeed a myth, all I can say is this: My brain doesn’t do the left-brain stuff. Numbers, algebra, equations, calculations, detail. Digits.

I was born without a left brain. Well, maybe a tiny rudimentary piece of left-ish cortex is in there. Even if the whole left brain/right brain thing is indeed a myth, all I can say is this: My brain doesn’t do the left-brain stuff. Numbers, algebra, equations, calculations, detail. Digits.

“Critical thinking,” says author

“Critical thinking,” says author